Surrounded by delicate flowers and colorful eggs, the rabbit has been associated with Easter for generations. Yet on surface appearance the rabbit and Easter don’t really seem to have a deep connection. What binds rabbits to this springtime holiday?

The rabbits connected to Easter are hares, which are technically not the same as rabbits. Having different body proportions, habitation patterns, and mating practices than your typical rabbits, hares don’t have that soft, fluffy bunny demeanor of your domesticated rabbit of today. Despite the difference, references to rabbits and hares are interwoven throughout countless cultures.

In Europe, this animal’s image is fluidly changing, being defined and refined. For some, the hare was seen as an image of fertility, love, and luck, while it was known by others to be shifty, uncertain, and a bad omen of future misfortune. Hares specifically (different than your average fluffy rabbit) were associated with witches who supposedly shape-shifted into this animal form and caused mischief like stealing milk and harming farm animals. Around the springtime, large bonfires were made as a means to scare the shapeshifting witches away from the towns and farms.

One 16th-century dissertation titled De Ovis Paschalibus Von Oster-Eyern (On Easter Eggs) cites that in the Alsace and Palatinate regions of Germany, an egg-laying hare was a part of springtime tradition. This paper also points out folklore traditions where the eggs were brought by foxes, roosters, and cuckoos as well, so there wasn’t just one type of egg-bearing Easter animal. German references to the hare are almost always male, but his egg-laying ability is most certainly female, giving the hare another mysterious quality. Where this story appeared is equally unknown, making for an even murkier origin story. The tradition spread in the Alsace and Palatinate regions and was part of an egg-hunting ritual where children would search for colored eggs outdoors.

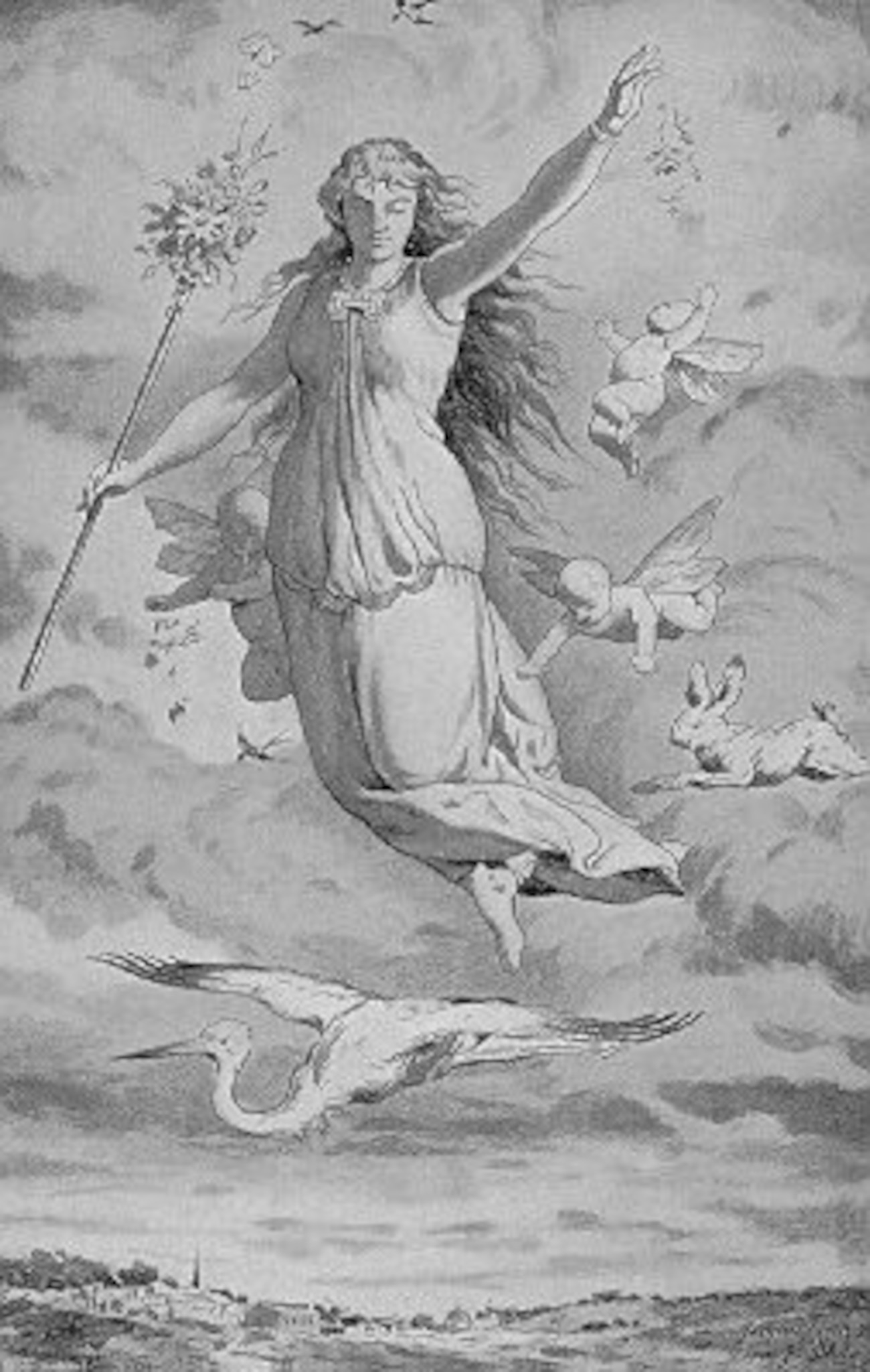

Yet references of hares to the springtime holiday of Easter didn’t really occur until the 19th century when Jacob Grimm (a famous folklorist and co-author of The Brothers Grimm) connected hares to a pagan springtime goddess. When writing Deutsche Mythologie, Grimm looked at Christian references to Germanic paganism. His source — an English churchman called Saint Bede — cited regional Anglo-Saxon celebrations of a springtime dawn goddess called Eostre. Grimm made the connection and called the goddess that frequented Germanic pagan celebrations Ostara.

Stemming from Grimm’s references, you’ll also find stories of the Easter hare being a loyal follower of Ostara. The story goes that the goddess found an injured bird that couldn’t fly and transformed him into a hare, so he could move again. There are many variations, but the story more or less goes that Ostrara seeing the hare’s despair allows the hare to lay eggs once a year (which happens to be Easter). This story is hard to track down in origin, and many groups support or detest this connection of hares to Easter and Ostara.

However, the connections of hares, fertility, and eggs were formed, and they do have a unique tie to springtime. The hare’s latter-mentioned symbol of fertility has merit as hares can become pregnant while in the last trimester of their first pregnancy, meaning the fertility rates and birth rates increase during this springtime breeding season. This surplus of hares coincides with a surplus of chicken eggs as well. Before the 19th and 20th centuries, surpluses of eggs accumulated around Easter (as eating eggs was prohibited during the Lenten weeks leading up to Easter). So the bounty of hares and eggs were, to some degree, quite easily visible cues in peoples’ surroundings. So the symbolism, to some degree, made itself a place in springtime, becoming an icon of sorts.

By the time German Lutherans immigrated to Pennsylvania in the 17th and 18th centuries, the lore around an egg-laying hare was firmly connected to Easter and proliferated onward. During the 19th century, references to Ostara only increased, including the later-mentioned egg-laying hare folklore and other versions of Ostara being driven into spring on a wagon pulled by hares. At this point, the Easter Bunny, (the differentiation between a hare and rabbits was dropped) had become a common seasonal figure. In Germany, the Easter Bunny, like Santa Claus, would go from town to town and give treats only to good children on Easter. Leading up to Easter, the tradition of writing to the Easter Bunny was a common German practice as well.

Yet these symbols, while common, weren’t universal symbols of Easter, but that was about to change in a literal sweet way. Germany had an established chocolate manufacturing business and crafting sweet rabbit-shaped chocolate became a fun way to break Lent and celebrate spring.

German Easter chocolate-making traditions came over with the German immigrants to the United States. Displays like Robert L. Strohecker’s 1890 giant chocolate bunny display in his drug store window really popularized the connection of rabbits and Easter to a wider audience outside of the German immigrant group. A perfect storm of mass production, commercialized milk chocolate, and the use of hollow figure chocolate molds saw the chocolate Easter Bunny spread far and wide, as the chocolate Easter Bunny made its way into mail-order catalogs, drug stores, and department stores.

From fables to chocolate, the road is a ubiquitous symbol hasn’t been linear, but this furry anima’s imagery is finally been established as the symbol of springtime and Easter.