Within the sea of beige (but delicious) Thanksgiving fare is a small pop of color comes into sight, but it’s usually reserved for the table’s nether region — the cranberries. Whether it be a haphazard chunky stack of homemade chutney or the eerily too smooth cylindrical shape of the jellied canned cranberry sauce, cranberries are never the most anticipated item. Sure, it tastes great on a post-Thanksgiving leftover sandwich, but most people are vying for a scoop of mashed potatoes or a slice of pecan pie before they consider this seasonal condiment. Yet why does cranberry sauce — year in and year out — make it to the holiday table?

Cranberries are very much indigenous and connected solely to North American soil. These bushes grow in wet, boggy climates in sandy soil, which limited their geographical success, but was a hardy plant inhabitants could rely on. Native Americans were recorded to have boiled fresh harvested cranberries with sweeteners and paired the thickened sauce as a tart-and-sweet spread to accompany cooked meats. The first recipe reference in the Colonial Era comes from Amelia Simmons’ 1796 cookbook, where she suggests eating cranberry sauce alongside roasted turkey and boiled onions (sounds quite similar to our Thanksgiving fare, right?).

While cranberries were quick to enter the New World’s culinary toolbox, there was little success at actually making the cranberry a more widespread food. Outside of small pockets of swampy chilly areas of New England, cranberries needed the cold, damp dormancy of a northeast winter, meaning cranberries did not thrive in any other place (later, as the country expanded, Wisconsin would be known as another big cranberry growing area).

Even in the late 19th and early 20th century cranberries were a localized, regionally specific product. The growing season was short, and the harvest and selling season was even more stinted. Cranberries would only come to the market from September through November. Fresh cranberries, with their short shelf life, had to be sold and had to be sold fast, making it a far from profitable business.

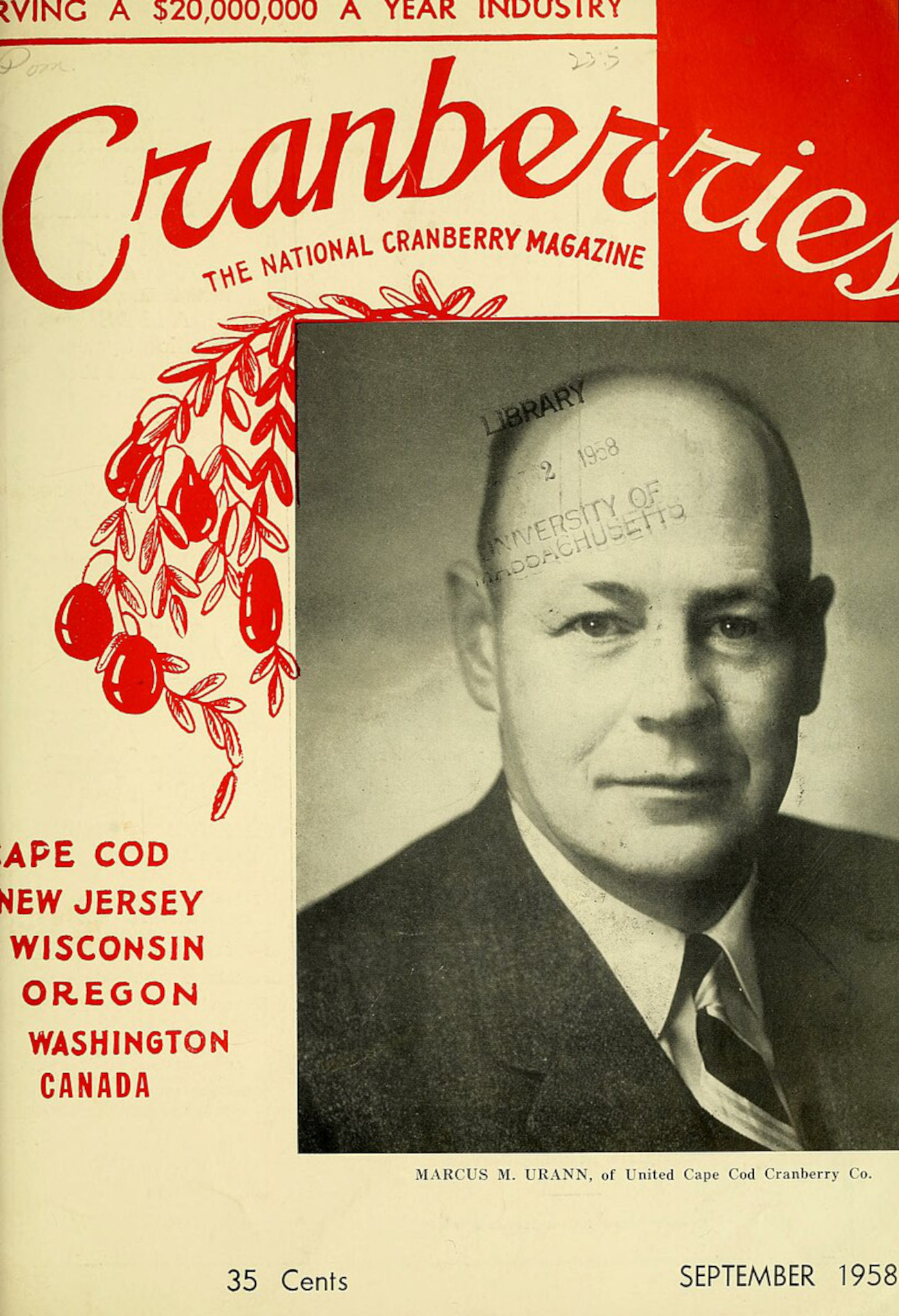

That is until ex-lawyer turned cranberry farmer Marcus Urann entered the scene. Throughout his interviews, Urann always espoused idealistic, altruistic goals, but he really was searching for profit, specifically finding a new way to make a profit. When he entered the cranberry business in the early 1910s the fresh cranberry market limited how much and where cranberries could be sold. The damage from wet harvesting (where you flood the cranberry bogs to remove the cranberries from the bushes), also meant a profit loss, as consumers didn’t want to buy broken fresh cranberries.

Ursann turned to a new mass-manufactured process, canning. Canning, or tinning, wasn’t a new process. Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, food was packed in a metal tin, sealed, and heated to remove bacteria —- however, it often came with uneven and sometimes deadly results. Early tin canning used lead solder to seal lids, which often led to lead poisoning. But as large manufacturers — like Libby — did canning on a mass scale without lead, the rates of lead poisoning and botulism decreased. Leaning into new mass-manufactured canning, Urann saw a way to get profit all year round. Seeing that fresh cranberries had a small regional market, Urann figured that if he could preserve the cranberries, via canning, he could distribute cranberries nationwide all year round.

Making canned cranberry sauce and juice meant it didn’t matter if the cranberries broke, meaning the damaged berries could also be utilized for profit. When Urann’s canned cranberry sauce and juice hit the market in 1912, there hadn’t been a product like that on a national scale. The once regionally specific New England cranberry made its way west and south, into cuisines that had (for decades) never encountered the cranberry. Under the name Ocean Spray Preserving Company, Urann sold his preserved cranberry crop. Initially, the company name he chose was the name of a Pacific Northwest canning company, and it was only after he started selling under the name Ocean Spray that he bought the name from the original company.

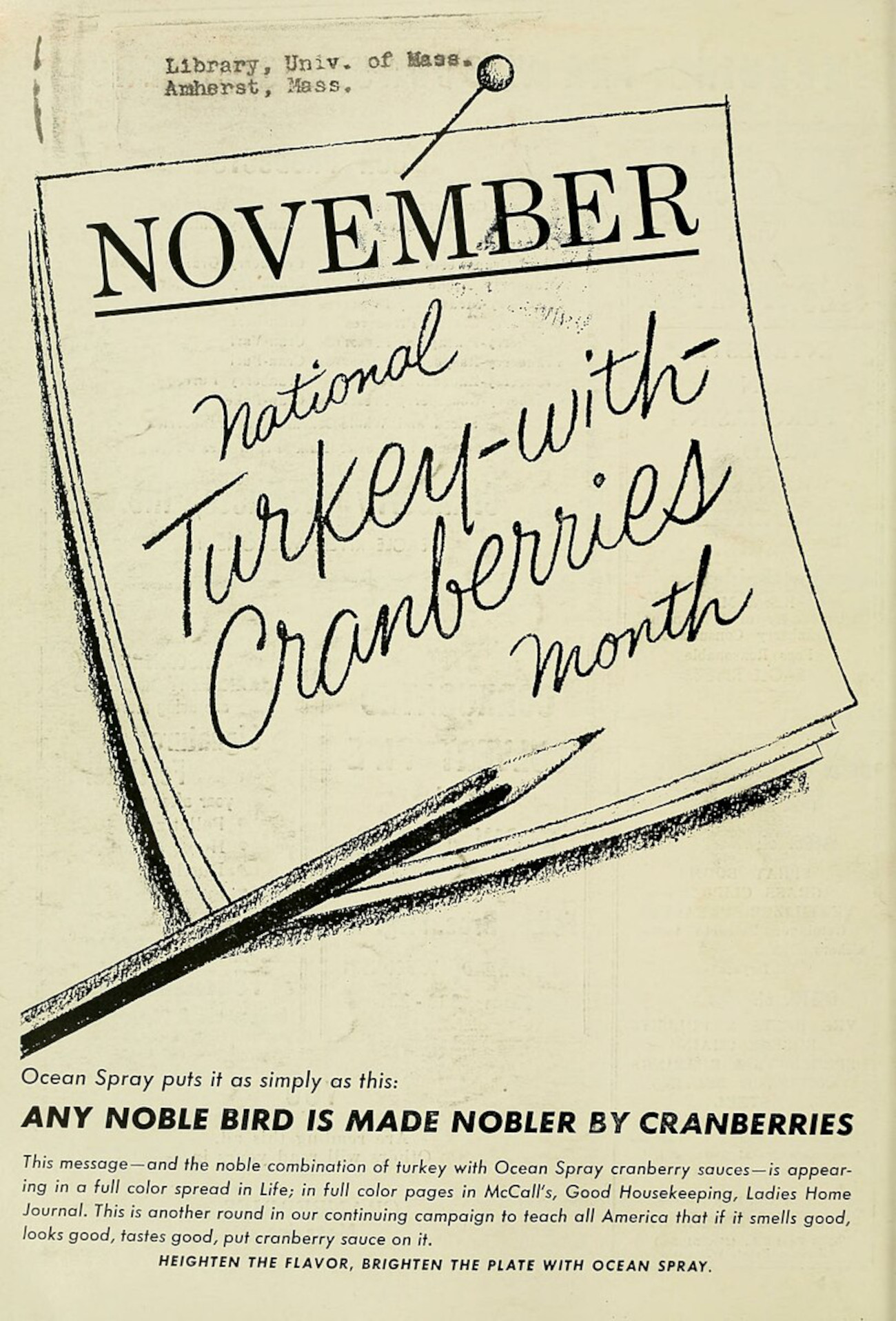

Urann used cannery and created a variety of products like cranberry cocktail juice (created in 1933) and the famous (or infamous) jellied cranberry log (which hit shelves in 1941). While jellied cranberry sauce may be a contested item of the Thanksgiving table, it is this cannery process that made cranberries and cranberry sauce a part of the broader nationwide Thanksgiving menu.

So while we homemade cranberry sauce enthusiasts may turn our nose up at a ridged log of jellied cranberry sauce, it was this processed cranberry matter that made cranberry a mainstay holiday item. Eating a smooth cranberry substance free of damaged, broken cranberries hit the hearts of 1940s Americans who still grew up in an era of Jell-O salad and aspic anything.

Ocean Spray can attest even today to Americans’ affinity for the smooth ridged log. While Ocean Spray does sell canned cranberry sauce, their smooth, jellied log beats other varieties. For every can of cranberry sauce sold, three cans of jellied cranberry sauce flies off the shelves. Nowadays, jellied cranberry sauce isn’t just reserved for the November and December holidays. There are seasonal spikes like the early fall, Super Bowl, and Easter, where communal crock-pot cranberry-based meatball recipes and a plethora of dips reign supreme. Cranberries are maybe more American than the beloved apples in an apple pie. They are a truly North American-specific crop that highlights the unique (and often unpleasant) weather of the land, showing that a bounty can come from an unforgiving harsh New World.