From Incan Delicacy To Fashionable Vegetarian Trend — How The Peanut Became Peanut Butter

It doesn’t matter if you like chunky or smooth; the salty, sweet, and roasted flavor of peanut butter is emblematically American, yet peanut butter wasn’t always standard-fare. The mighty peanut has been a globetrotter, crossing seas and spreading its way into culinary traditions and eventually becoming the condiment Americans know and love today.

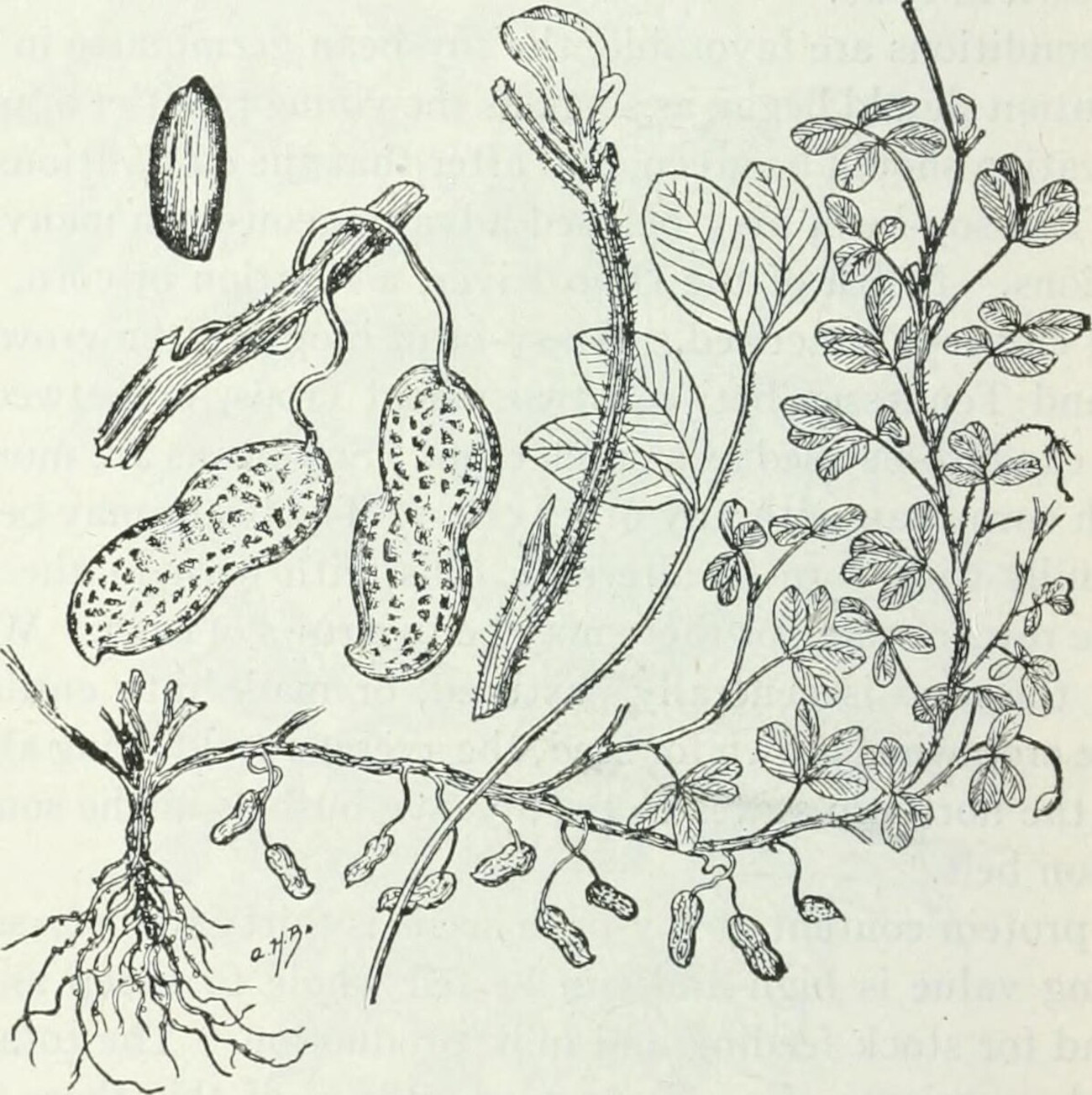

Little credit is given to the Incan civilization, who were the first to cultivate and consume peanuts. Spanish conquistadors noted that the peanuts were never eaten raw, but were instead roasted, ground, and blended with honey to create a stiff marzipan-like consistency.

Taking this food with them, the Spanish brought the peanut with them on their voyages, and the peanut found its way to the shores of East Africa, where the peanut began to be used in regional recipes. With the devastating and profitable triangle trade, the peanut went back across the Atlantic and hit the shores of the Caribbean as well ass trade posts and bases established on the shores of the Eastern seaboard.

Fast forward in time, and eating peanuts was becoming more and more popular. Agricultural scientist George Washington Carver’s literature about peanuts gave a good, in-depth look at how he saw peanuts fitting into more American cuisine. But out of the hundred-plus uses for peanuts, there was little evidence of the spreadable condiment we’re familiar with today. For one, peanuts aren’t particularly digestible unless ground or chewed very well, and the roasting and grinding process was not something done in one’s home. To make an peanut spread, one would have to thoroughly clean a meat or coffee grinder for the peanut grinding process.

Industrial inventions at the turn of the century were a turning point for eating peanuts. Canadian inventor Marcellus Gilmore Edson was one of the first to patent a peanut butter manufacturing process by roasting and grinding peanuts and then mixing the paste with sugar until it formed a semi-hardened consistency.

At the turn of the century, Seventh-Day Adventist John Harvey Kellogg was eccentric about many things, one of which was his dietary beliefs practiced in his Sanitorium at Battle Creek Michigan. Kellogg’s no spice, no salt vegetarian way of eating embraced this peanut butter as a meat-free alternative to getting protein. His elite clientele proliferated this peanut butter spread as a couture fashionable food. In the media, Kellogg-influenced elite peanut butter consumers inspired the media to promote this new food item. Advertisements for alcohol-infused peanut butter were a brief thing in newspapers and magazines. Although alcohol was not Kellogg-approved, media outlets had creative licensing to make it sound posher to a degree. These recipes described peanut sandwiches with chopped peanuts mixed with splashes of alcohol adorning bread as a new stylish food, but grinding peanuts for such a recipe just wasn’t interesting nor practical for the American population of the time.

Manufacturers of peanut butter did increase, especially during World War One when meat was rationed on a national scale. Yet people still did not jump on it nor enjoy it. At the time the oil from the peanuts separated during the grinding process. If you bought a jar of peanut butter at the turn of the century you were advised to frequently stir the oil back into the ground peanuts or else the entire mixture would spoil.

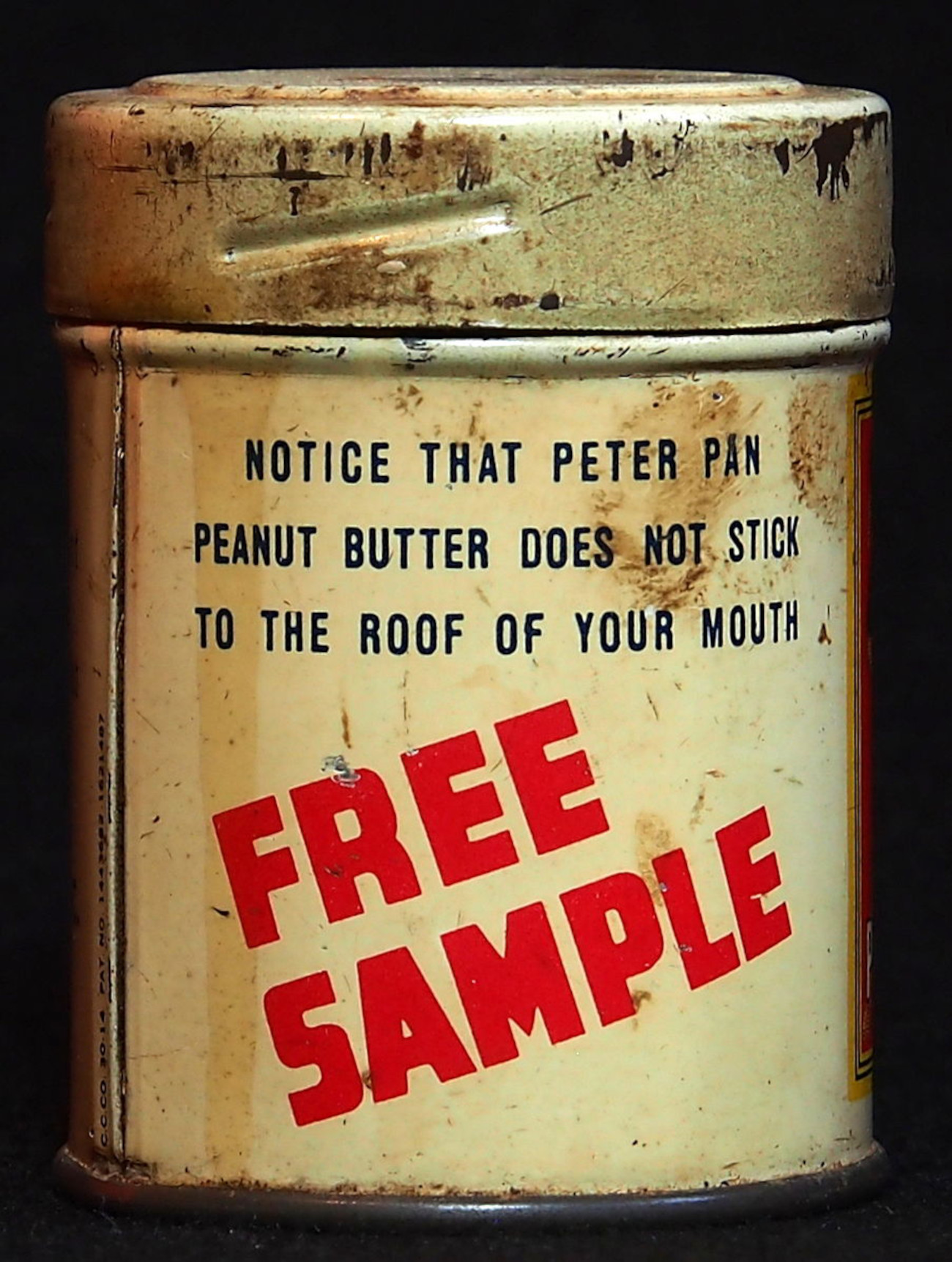

It wasn’t until the early 1920s that Joseph Rosefield filed a patent for hydrogenating oils, making oils, which were naturally liquid at room temperature, become solid at room temperature. Applying hydrogenation to peanut butter was a game changer in how people consumed peanuts. The hydrogenated oils stayed emulsified with the ground peanuts, making it shelf-stable for longer. With a longer shelf life, peanut butter could be manufactured and distributed on a much larger scale. Removing the oil mixing process was a bonus for customers. Around the same time, peanut butter was made creamier and didn’t have the stick-to-the-roof-of-your-mouth quality to it anymore. The Great Depression bolstered peanut butter sales as peanut butter was a frugal protein that could be utilized in both sweet and savory recipes (peanut butter onions anyone?).

But it wasn’t until World War Two, when manufacturer Skippy sold peanut butter in mass to the US government. The government sent the spread over to troops overseas, and becoming a wartime food was a game changer. Peanut butter, paired with grapelade (fruit plus the suffix lade was a term for jellies throughout the early 20th century), and pre-sliced bread brought a sweet and salty combination into a quick, satisfying meal in handheld form. After the war, sales of peanut butter skyrocketed, and it was further cemented, not to the roofs of our mouths, but into the culinary dialogue of true American food. And while other countries, like India and China, produce and harvest more peanuts, America surpasses any other country in peanut consumption. It’s a mainstay in American pantries even to this day.