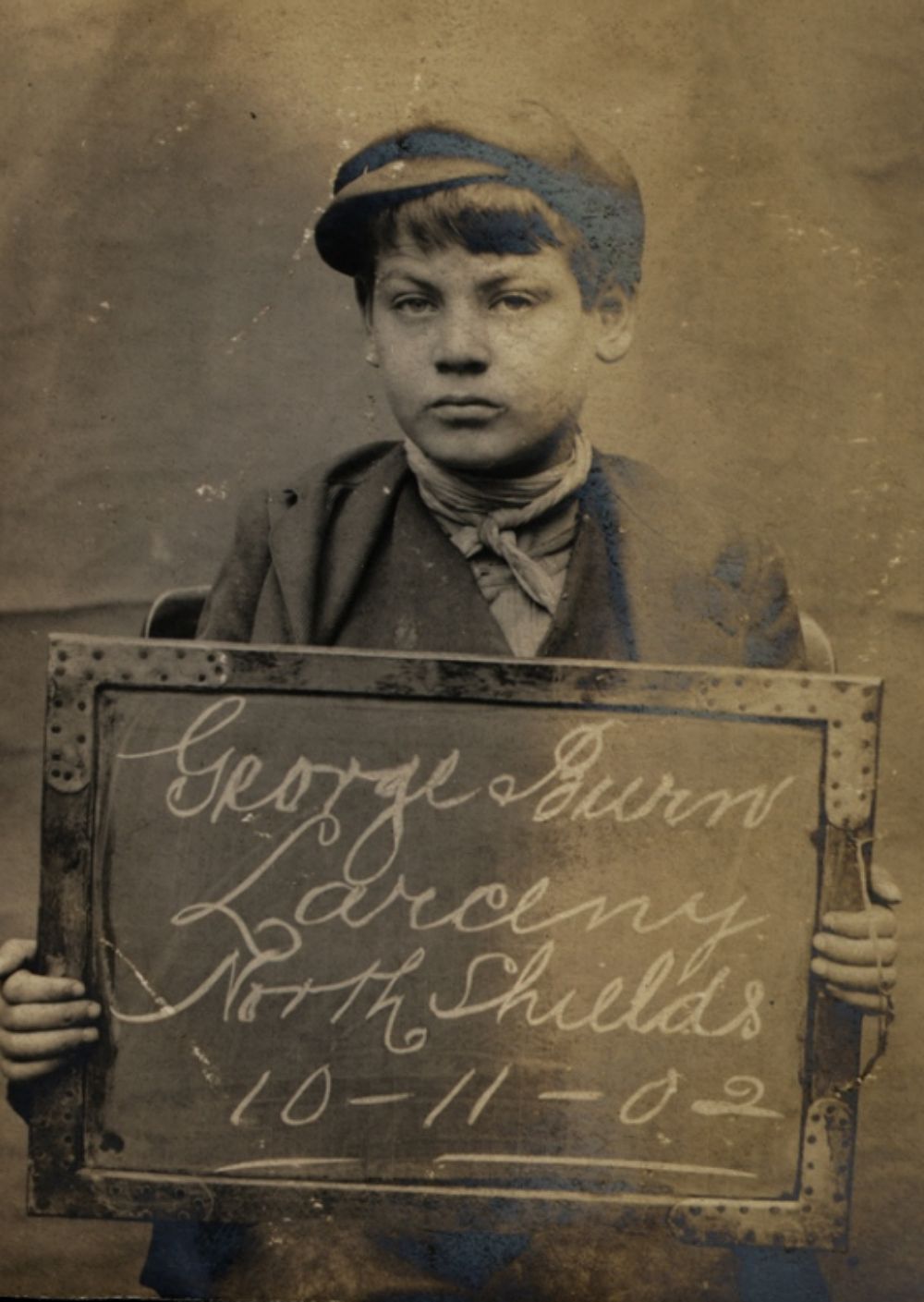

The Victorian era was a time of invention and industrialization. But, alongside the progress that was made were the forgotten souls who lived life in filth, poverty, and with little to no public services to help them out. With the extreme disparity of wealth many impoverished people ended up in jail, having made ends meet by gambling, stealing, or other crimes.

Prisons and jails at the time were often rudimentary in terms of shelter, with some facilities offering little in the way of protection from the elements. Considering all this you might assume that the food prisoners were served back then was awful, but that wasn’t always the case.

A modern study of prison records in Victorian England examined the weights of prisoners (both male and female) upon starting their sentences, when they were moved to other facilities, and when they were released. Over the course of their sentences most prisoners maintained their body weight, but 7% of men and 13% of women actually gained weight in the slammer.

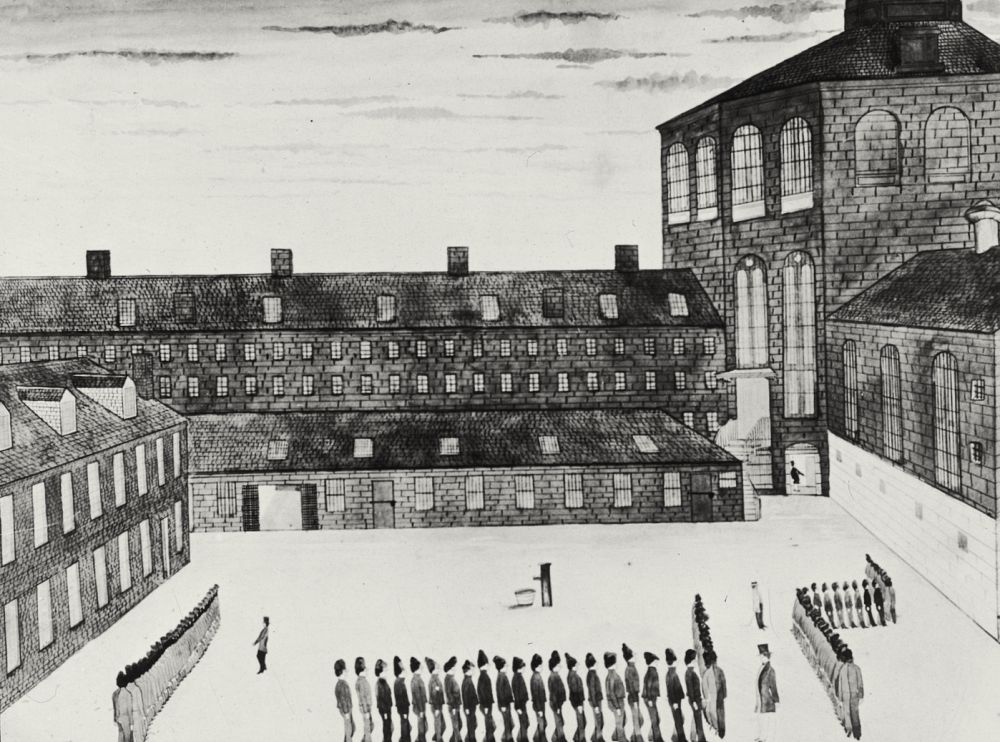

This weight gain is pretty incredible when you consider that the food was rumored to be lacking. Not only that, but prisoners of this time period would have been given a great deal of manual labor to do as penance- even if the labor served no real function. This means that prisoners moving cannonballs across the room all day (an example of the useless labor) or pumping water or doing laundry (the more useful kind of work) were still gaining weight despite the intense work they were being put through each day.

The longer one’s sentence the better the food was (and there was more of it, too). For short sentences, say a month or two, the inmates got worse food because they weren’t going to be there that long and it was considered a waste. But, for those serving longer terms the food was more nutritious.

Bread, potatoes, fish, and milk were all staples of prison food in England at the time. But, there was another food that prisoners hated: stir about. It sounds like a lumpier version of gruel and it’s made from cornmeal, oatmeal, water, and sometimes a pinch of salt.

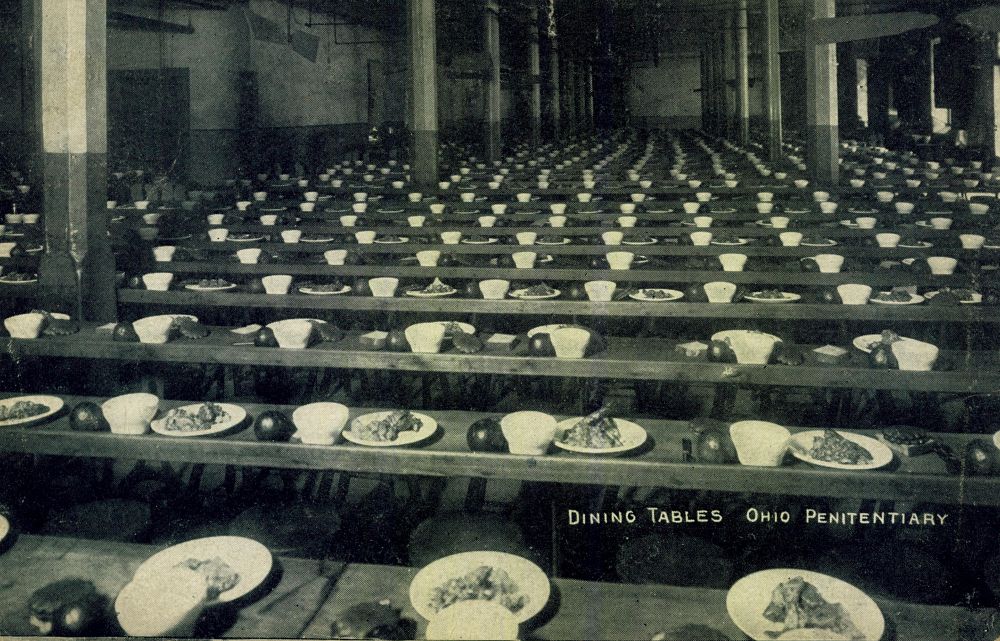

How much and what kind of food to serve prisoners was a topic of hot debate in the 19th century. On the one hand, it was seen as cruel to starve the prisoners and there was a charge of maintaining the welfare of the inmates.

On the other hand it was thought that serving too good of food would be an incentive to commit more crimes. The compromise in many locales was a diet that was nutritious, but bland and unchanging. Thus an inmate might look forward to bread, cheese, gruel, suet, and potatoes every week, with little to vary the experience from day to day.

Up until the end of the 19th century, lobsters were fed to prisoners as they were seen a poor people’s food. The great numbers of lobster at the time contributed to the opinion that they were like the mice of the sea. They also viewed lobsters as bottom feeders, which didn’t help the lobsters’ reputation.

Contrary to how we do things today where lobster is one of the more expensive dishes you can order at a restaurant, lobster was served to prisoners, enslaved people, and indentured servants in the U.S. throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. It wasn’t until canned lobster was created that the sea creatures began to be eaten by regular folks. But, even as late as the end of the 1800s it was still seen by many as a poverty food that only the desperate would consume.

At the time it was common to cook lobster once dead, unlike the way lobsters are cooked today (boiled alive). The difference in preparation could explain the change in attitude. Lobster have unique enzymes in their stomachs and this means that when they die their flesh rots very quickly and can make people sick if they eat it. Thus, if you were eating lobster in the old days it would have had to be either extremely fresh or canned in order to be a safe food.

A record of prison meals from the 1870s in Philadelphia shows that the inmates were given stews with meat and vegetables for many meals, with a generous supply of (unbuttered) bread, tea, coffee, cocoa, and sugar available to them. More generous portions of meat, along with precious butter for the bread, were reserved for inmates that were ill and under a doctor’s care. It may not have been a culinary delight, but it does sound hearty enough to sustain the prisoners fairly well.

This doesn’t mean that all prisons served enough food to their charges or that the food tasted good, but on the whole it seems that the Victorians did their best to feed inmates well by the standards of the day. The same could not be said of orphanages and workhouses, where the food was kept to a minimum and failed to offer the nutrition needed to sustain the inmates (bread, broth, or cheese were common meals in the workhouses).