Halloween today, with its door-to-door (or now car trunk to car trunk) trick-or-treating, has derived from a complex and intertwined history. Halloween, up until recent times, was one of spiritual protection, purification, and prayer. The Celtic holiday (called Samhain or summer’s end) marking the beginning of winter was celebrated by making huge bonfires and donning animal masks to disguise oneself against the spirits. Later on, the seasonal change of harvest time underwent a Christianization, becoming a prerequisite of November 1st’s All Soul’s Day. All in all, the last day in October was a time to ward away and guide spirits away from humans, as well as protect oneself from evil spirits or bad luck. However, the souling rites of the past became a bit different as they crossed the Atlantic and into the States, became more mischievous, until one woman sought to change it.

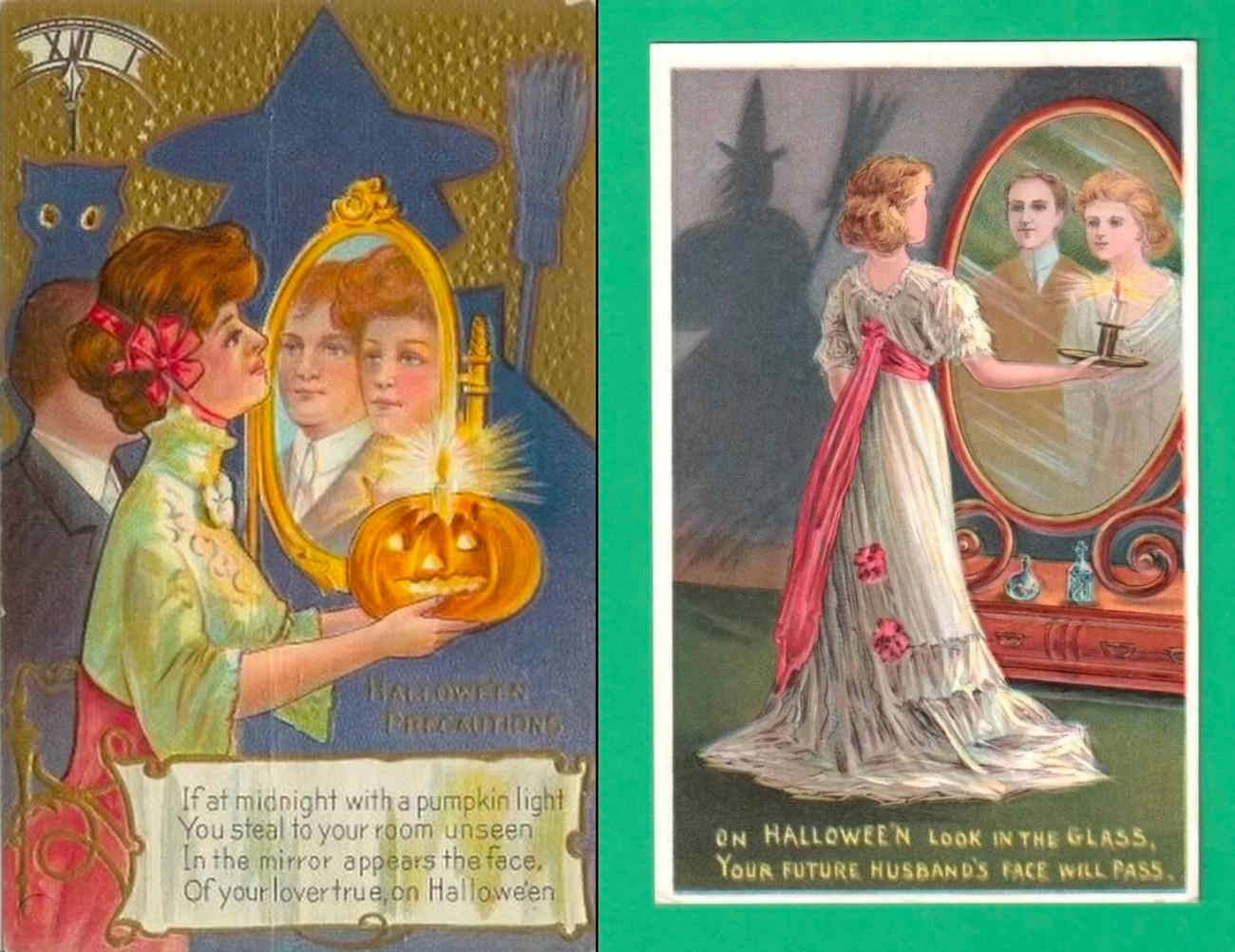

While it was a time for masquerading, prayer, and ritual gave way to lighter festivities. The 19th century and early 20th century saw the rise of ritualized fortune-telling. With the veil between the living and the dead being the thinnest, people used apples, mirrors, candles, and cards as ways to predict their fate or future. These sorts of party games sound harmless; the activities that sprung out during the turn of the century were not so innocent.

Door to door trick-or-treating was more of a door-to-door slue of property damage. Vandalism and mischief don’t necessarily describe the havoc recorded throughout the US. It was well recored in Kansas newspapers, where Halloween tricks weren’t a one-time occurrence and started weeks before the actual day. Tricks were more akin to serious vandalism and arson, tampering with cars, streets, streetlights, and houses. Some boys were maimed and even killed by falling victim to their own pranks near passing cars or on train tracks. The bonfires of the Samhain tradition were transformed into dangerous bonfires started on the porches of townspeople.

While people hired neighbor watchmen and had men patrol with dogs, it did little to curb the vandalism. This issue wasn’t just an isolated problem in Kansas City, as it was an issue among the youth, especially in the nearby city of Hiawatha. A resident, Swiss-born Elizabeth Krebs, like many of her fellow townspeople, was tired of the mischief. Founder of the Hiawatha Garden Club, she opened the windows on every November 1st, only to see her prize-winning flowers ripped apart and destroyed. For someone who had lost two of her three children to illness, Krebs had funneled a lot of her energy and passion into her gardening, so she was quite motivated to stop the annual destruction.

Wanting to protect her garden, in 1913 she set up a party at her home full of games and treats to distract the rowdy and mischievous children. Initially, Krebs thought it was a success. Yet when the next day rolled around, she saw that her garden was still torn up and several things were set ablaze on the street, one of which was a city mail carriage.

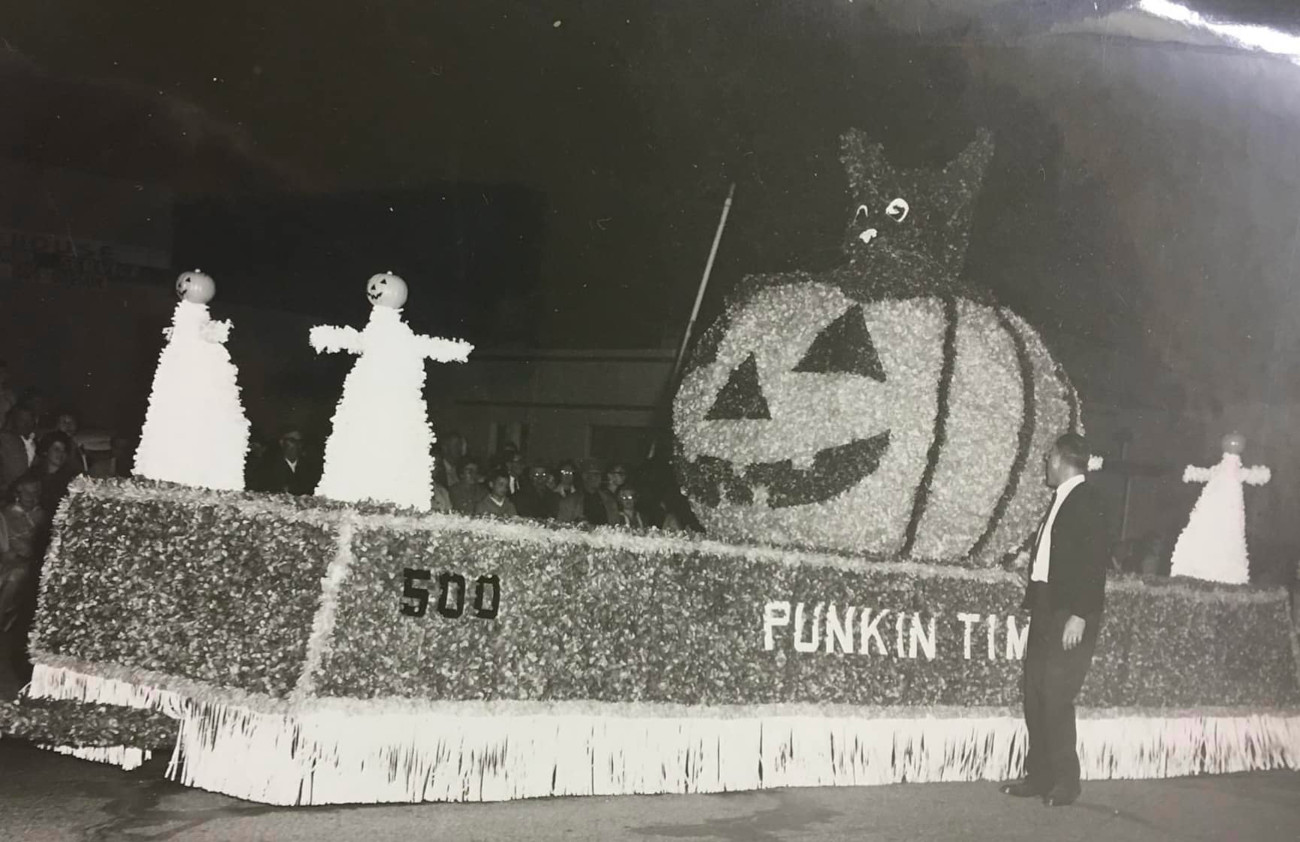

Disappointed but still determined, Krebs went on devising a bigger party, this time getting local officials and businesses involved. The event in 1914 titled “Hiawatha Halloween Frolic” had the whole town show up, participating in games, costume contests, and a parade. Children of all ages, distracted with food and making parade floats, participated in the event. Come November 1st, the reports of vandalism decreased drastically and Krebs’ garden was untouched.

Krebs’ Halloween festivities were mirrored throughout the state, drastically reducing crime and property damage. The parade and party started by Elizabeth Krebs is known as the US’s oldest Halloween parade tradition and is still celebrated in that city annually. In its preceding years, it developed with several festivals, including a beauty pageant crowning an annual Halloween Queen. This holiday legacy has given Elizabeth Krebs the title of the Mother of Halloween of the city.