For many centuries, fine china has been held in high regard, with families choosing to hand down this type of heirloom through the generations. One of the most sought-after styles of glaze on china sets during the 19th and early-20th centuries was the mesmerizing lustreware finish. This metallic glaze created opulently shimmering finishes, but the technology goes all the back into Medieval times.

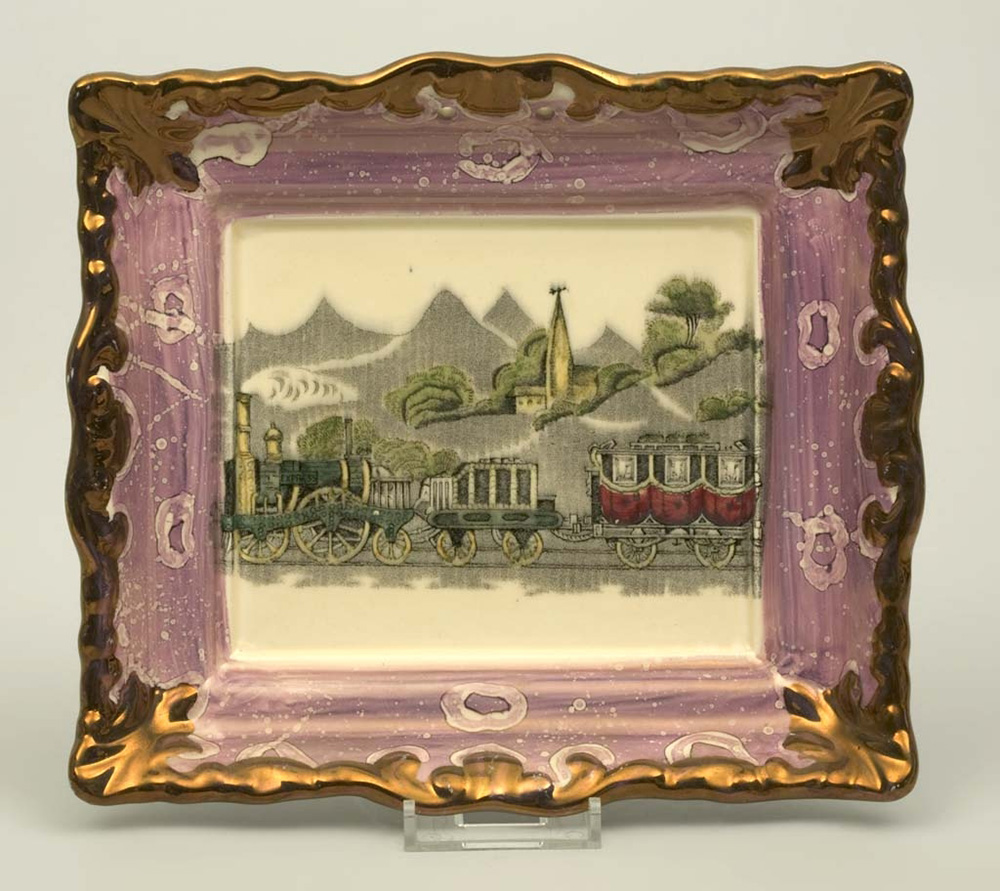

The process of applying a glaze to pottery takes a lot of patience and knowledge, as any imperfections in either the formula or the process can spoil the finished product. However, the finished effect for makers of ceramics was worth it because it could make a piece look gilt or like it was made from copper, or even a multi-hued translucent pearl finish could be the result- all of which commanded higher prices than regular painted or transferware.

The oldest known pieces of lustreware are from the 9th century from what is modern day Iraq. While the process does involved metals, namely copper, lead, and silver, the golden finish is achieved using no actual gold. At the time this was seen as a feat of chemistry alchemical in nature and was a marvel of craftsmanship that spread from Iraq to China and beyond.

The first countries in Europe to begin using this style of glaze were Spain and Italy, with both countries producing these pieces into the Renaissance period. The popularity of blue and white pottery and china from the 1600s onwards dominated the market, but in the late 1700s a revival of lustreware took place in England and France, setting off another 150 years of popularity for this style.

The opulent royal houses of Europe in the 1700s were fond of lustreware, and enormous sets of bone china were crafted to include niche pieces that most people today have never seen. Such pieces as ink blotter boxes, bone dishes for placing refuse bones on at the table, finger bowls, and a huge assortment of condiment servers were among the massive inventories of lustreware in the cupboards of the very wealthy.

Some highly collectible forms of English lustreware are so-called “moonlight” pieces, which feature an allover metallic glaze in pinks, lilacs, or oranges. Two of the most well known makers are Sunderland and Wedgwood.

As mass production brought down the prices of luxury goods, more middle class families were able to afford things like lustreware china. Germany, Bohemia (modern day Czech Republic), and Vienna became centers of lustreware production in the 19th century, in addition to France and England. Some of the oldest examples of lustreware may not be marked, and in many countries maker’s marks were not required until the 20th century.

Even at the start of the 20th century this style was still quite popular. As the century wore on such opulence was not only unaffordable due to the Great Depression, it was increasingly considered out-of-date and stuffy. However, many Art Nouveau and some Art Deco china patterns still featured lustreware decorations.

Lustreware was less common following World War II and the sheen was in contradiction to the modern styles which emphasized usefulness, saturated color, and durability. But, even in the 1950s and 1960s popular tableware sets were made in this style, most notably the Fireking apricot glassware which featured a finish meant to emulate the moonlight lustreware of a century before.

Today, the look is still popular among a certain set, but is less practical for heavy usage. The gold parts of the glaze, applied in sparing fashion in a thin layer, can wear off when used often. And, you cannot put lustreware items through the microwave. As a side note, you should never put any vintage or antique pieces of china or glass in the microwave as they were not made to withstand the concentrations of heat that microwaving produces.

Today the most valuable pieces of lustreware are from the 19th century and earlier, though fine examples from any era can command good prices if given the right audience. Some of the most desirable pieces of lustreware were made by Wedgwood, Noritake, and Staffordshire makers like Sunderland. Prices can range from only $10 all the way up to $1,000 per piece for large and fine pieces of Wedgwood, for example. Staffordshire pieces can sell in the hundreds each, while complete sets of lesser-known makers can sell for the same price.